lessons on reading

“reading is at the threshold of our inner life; it can lead us into that life but cannot constitute it”

It’s been a few weeks since I stepped onto my little podium on the internet and shook the world with my audacity.

Yeah, I’m Him, the guy who hasn’t read any new books since June.

In case you missed it, I’ve been exclusively re-reading books this summer in an attempt to detox my relationship with reading.

Overall, this exercise has been going great. I’ve learned a lot about my reading preferences and I’m also working to build a better literary consumption routine.

Reading my favorite books for a second time has brought me so much joy. Being reunited with beloved characters—with whom I've shared moments of pain, growth, and triumph with—has felt deeply comforting.

But I do have a confession to make.

I broke my self-imposed rule.

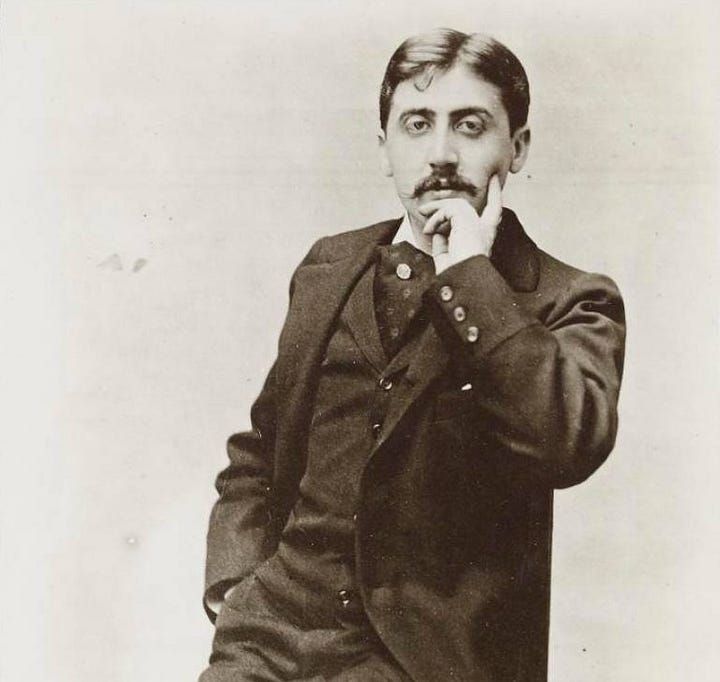

I decided to supplement my reading detox with lessons on how two prominent literary figures, John Ruskin and Marcel Proust, approached reading.

So yes, I read one new book.

The book was aptly titled On Reading and is composed of Ruskin’s Lecture I. Sesame. and Proust’s rebuttal to said lecture.

Not even a page into Proust’s preface, I realized how my lack of trained discipline—a byproduct of a steady post-grad diet of modern novels—encourages my eyes to skim over what’s written in front of me. I often found myself re-reading passages over and over again, chipping away at the text until the words finally made sense in my heart. On Reading lovingly demanded my full-focus: though only a hundred pages long, it took me a couple weeks to finish.

But the lessons I learned! Proust and Ruskin helped me rediscover the purpose of books in my own life through tackling different angles of the same, ever so elusive question of why do we read?

In the end it was all so worth it, and I’m excited to share what I learned on reading, from reading, the perspectives of two great literary minds.

Ruskin argued that books are valuable because they allow us to pick and choose conversations with the greatest minds of all time.

Books not only enable us to converse with great people, they often contain their most impressive wisdoms as well. Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Aurelius’ Meditations.

The life’s work of a genius condensed into the palm of our hands. It’s impossible to deny the wealth of knowledge contained within these books.

And so, in typical academic fashion, Proust decided instead to disagree with the semantics of Ruskin’s claim, arguing that reading and conversation fulfill different objectives.

Ultimately, Proust used this disagreement as a springboard for his thesis on the importance of solitary reading and thinking. He emphasized that the introspection and deep understanding gained from reading in solitude provides a depth of thought that conversation simply cannot replicate:

“Reading cannot be equated like this to conversation, even a conversation with the wisest of men; that the essential difference between a book and a friend is not their greater or lesser wisdom but the manner in which we communicate with them—reading, unlike conversation, consists for each of us in receiving the communication of another thought while remaining alone, or in other words, while continuing to bring into play the mental powers we have in solitude and which conversation immediately puts to flight; while remaining open to inspiration, the soul still hard at its fruitful labors upon itself.”

Proust acknowledges something we’ve all felt numerous times in our life: that frustrating experience of being unable to find the right words to describe a feeling or revelation adequately to another person.

But maybe that’s normal.

Perhaps it simply is not possible to ever fully convey, nor understand, really complicated thoughts to/from another person. While I understand this isn’t the most optimistic perspective, it is a rational one—our thoughts are the totality of our experiences, and unless someone has lived the exact same life that we have, conversation will always be limited by subjectivity.

I’m not saying (and neither is Proust) that this is enough of a reason to abandon all attempts at understanding others’ complicated thoughts. It’s not futile! While total clarity may be difficult to achieve, we can still attempt to stir something up within the other person. It just may be hard to do in conversation where the “spiritual blow is softened”:

“In conversation… communication takes place through the mediation of sounds, the spiritual blow is softened, inspiration and profound thought are impossible.”

Proust argues that our minds are better suited to understand these more complex thoughts in solitude. Because when you’re in the comfort of your own bedroom—shielded from the necessities of social norms, propped up with pillows inside your comfy sheets, a piping-hot cup of chamomile tea on your bedside table that you’re letting cool but will inevitably forget to drink—you’re better situated to connect deeply with the beautiful words in front of you:

“Solitude only allows us to put ourselves into the state in which the author found himself.”

Good literature is not a self-help book; it’s not going to spit out a listicle of how to improve your habits. It’s going to take effort to understand.

But a good writer, tasked with conveying their burning realization1 with a finite vocabulary, can take you almost all the way there:

“The end of a book’s wisdom appears to us as merely the start of our own, so that at the moment when the book has told us everything it can, it gives rise to the feeling that it has told us nothing… Reading is at the threshold of our inner life; it can lead us into that life but cannot constitute it.”

And what does a good reader do? He listens with his eyes and thinks with his heart to add the final piece to the writer’s message: one’s own experience. Through trusting in his “mental powers”, the good reader not only understands the author’s message, but has the strength and desire to mold it into something unique, genuine, and original.

Proust, in his essay, addressed the question of why is reading so great at generating unique thought?

On the other hand, Ruskin offered his perspectives on a more philosophical question: what does society have to gain from reading?

The short answer is that reading develops a more empathetic society.

Ruskin was extremely frustrated with the superficiality and vanity plaguing his mid-19th century England:

“Practically, then, at present, ‘advancement in life’ means, becoming conspicuous2 in life; obtaining a position which shall be acknowledged by others to be respectable or honorable…In a word, we mean the gratification of our thirst for applause… we want to get into good society, not that we may have it, but that we may be seen in it.”

He claimed that this infatuation with public image coincided with the popularity of fleeting, contemporary writings. Ruskin characterized these pieces as “books of the hour”—works that are temporary (letters and travel diaries), sensationalized (news), and specific to the present moment (modern novels).

In contrast, “books of all time,” as the name suggests, offer timeless wisdom and insight but require more effort to understand. Ruskin believed that reading these books, which have not only stood the test of time but also often present challenging or controversial ideas, was well worth the investment.

Because the purpose behind reading is not to confirm what you already know or get riled up by headlines, but to gain perspective:

“Very ready we are to say of a book, ‘How good this is—that’s exactly what I think!’ But the right feeling is, ‘How strange that is! I never thought of that before, and yet I see it is true; or if I do not now, I hope I shall, some day.’”

To Ruskin, the ability to understand one another and empathize with your neighbor was the single most important factor in fostering a more progressive society.

Yet, in a world that prioritizes status, wealth, and pleasure, there is little room for perspective and empathy. And thus, Ruskin held the pessimistic view that his modern society, with its priorities all out of whack, had lost its ability to engage with these “books of all time”:

“It is simply and sternly impossible for the English public, at this moment, to understand any thoughtful writing,—so incapable of thought has it become in its insanity of avarice3.”

Fast-forward to 2024, and I’d argue that our modern, scatterbrained approach to reading continues to reflect and contribute to our superficial society—a society filled with people regurgitating trends and extremist rhetoric without genuinely reflecting on their own opinions.

I’ll end with this excerpt on what Ruskin believes differentiates humans from animals:

“You have heard many outcries against sensation lately; but, I can tell you, it is not less sensation we want, but more. The ennobling difference between one man and another,—between one animal and another,—is precisely in this, that one feels more than another. If we were sponges, perhaps sensation might not be easily got for us; if we were earth-worms, liable at every instant to be cut in two by the spade, perhaps too much sensation might not be good for us. But being human creatures, it is good for us; nay, we are only human in so far as we are sensitive, and our honor is precisely in proportion to our passion.”

Contrary to popular belief, crying never killed anyone.

He who weeps may be sad, but he weeps because he is more human, because he cares deeply—so deeply—that words alone are not enough to express his passion.

The common message I’ve taken away from both Proust and Ruskin is the importance of being someone who generates their own passions—someone who understands, from within, what is truly worth fighting for.

Reading, at its best, demands time, introspection, and vulnerability to engage with challenging ideas and emotions. It pushes us to confront our own ideas, question our beliefs, and grow in ways that other forms of media or communication simply cannot replicate.

Reading is hard.

But then again, have worthwhile things in life ever been easy?

Or as Ruskin beautifully writes, “the piece of true knowledge, or sight, which his share of sunshine and earth has permitted him to seize”

Conspicuous: the fact of being easy to see or notice, and likely to attract attention

Avarice: extreme greed for wealth or material gain

I loved the breakdown of how status-seeking inhibits empathy & reading! I’ve been more intentional about my consumption too, especially since it seems most social media content is about shallow amusement rather than adding something to new to our own thoughts, like you said